In This Complex World, Music Embraces Us: A Conversation Between Ichiko Aoba and Michelle Zauner

Music is a “station” where people can come together, no matter their differences

2025/11/11

Fairies, daydreams, and magic. Ichiko Aoba’s music allows the listener to step outside of their usual box and enter a space where they can breathe, with an imagination that reweaves the threads between different living beings, from humans and whales to fungi.

Michelle Zauner of Japanese Breakfast is a Korean-American musician born to a Korean mother and an American father. Japanese Breakfast’s debut album, Psychopomp, poignantly reflects the process of dealing with the loss of her mother to cancer and her memories. She is also the acclaimed author of Crying in H Mart.

In life, everyone must inevitably go through sadness, hardship, and boredom. Aoba and Zauner create music that leans into the instability and unreliability of everyday life and captures various phenomena in all their ambiguity; they embrace things in a multidimensional manner. As such, the two continue to leave their familiar surroundings and experience many cultures through touring or studying abroad. How do they understand themselves through living with music as artists? How do they try to love other people and the world?

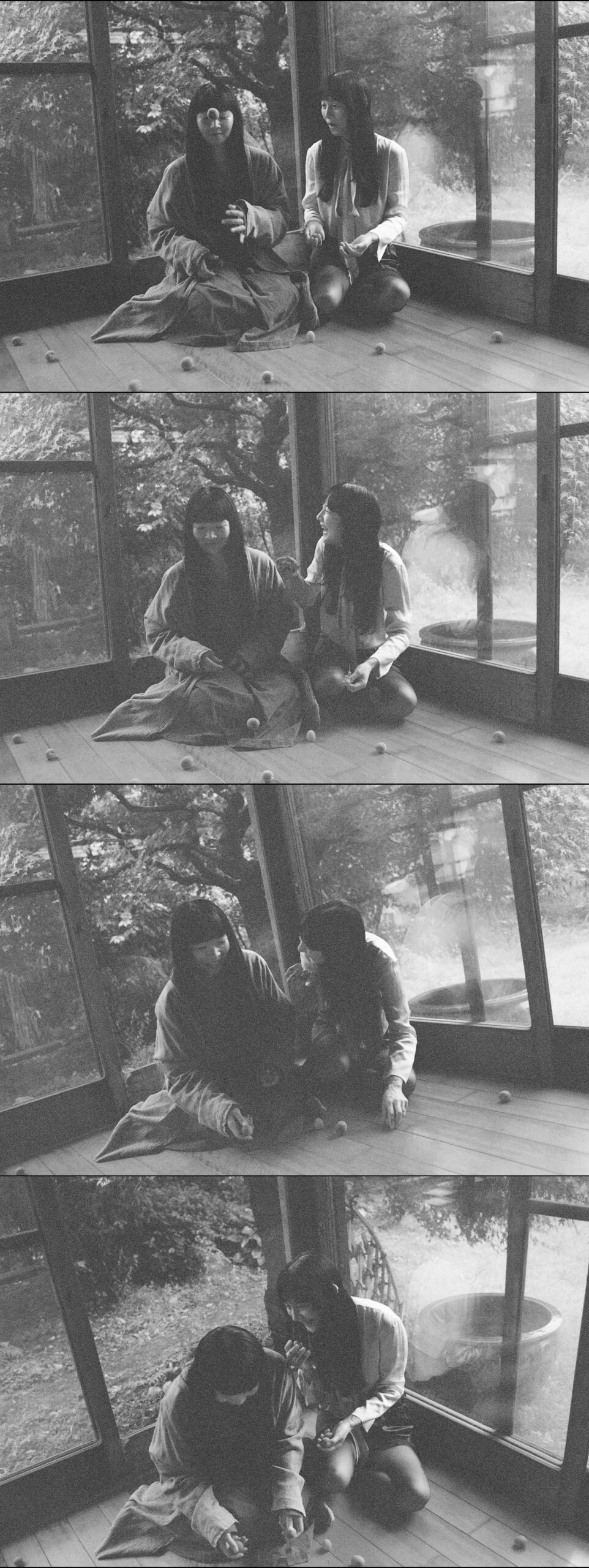

Aoba, temporarily back in Japan during her Luminescent Creatures World Tour, and Zauner, also in the country for The Melancholy Tour, spent a few hours together in a house blending Eastern and Western styles. With a glint in their eyes, they shared white, fluffy coconut-flavored warabimochi and ripe cherries while discussing how they take on each day without giving up in the face of the endless uncertainties of love and life.

─I’m so happy I get to talk to you both today. I’d first like to know how you two met, as well as your impressions of each other’s work.

Michelle Zauner: I first heard Ichiko’s music when I was in Sweden; it was recommended to me on some Spotify playlist. It was a big trip for me because it was one of the first times I traveled alone. When you travel alone, your senses are very heightened.

I was usually with my husband or bandmates after my mom passed away, so I was nervous about traveling alone. That was the moment I discovered her album. I would just walk and listen to her music. It was so cinematic, and it really kept me company. I feel like I was able to connect so deeply with it because I was alone and in a foreign country. It was a very moving and special experience to feel that close to her music. That’s why it was my dream to get to meet her and play a show with her.

(Points at the album cover of Mahoroboshiya by Ichiko Aoba) It’s funny because I think she kind of looks like Ariana Grande.

Ichiko Aoba: (Laughs) Really?

─I’m assuming you didn’t understand the lyrics when you first heard Ichiko’s songs. It sounds like you were drawn to her melodies rather than words.

Zauner: I was listening to a lot of ambient music at the time. I needed music that was very gentle, calming, and cinematic. It was so soothing and healing for me to listen to on a rainy day, like today, in Sweden.

─It’s very sweet and fitting that you stumbled upon her music while you were alone in Sweden. Ichiko, how did you discover Michelle’s music?

Aoba: Japanese Breakfast played at Fuji Rock Festival in 2022. I didn’t know about her at the time, but Kodai Kobayashi, who’s photographing us today, told me about the live stream. I remember watching her through that. Right after that, Michelle asked me to join her tour in Los Angeles and New York as the opening act. I remember being very happy, thinking, “I’m meeting her in person.” I read her book, Crying in H Mart, listened to her [2021 album], Jubilee, and boarded the plane to go meet her.

We had just started coming out of the pandemic at the time, so I was getting booked for many shows abroad. It was exciting to see how this previously unknown world was unfolding, but at the same time, it made me vaguely anxious. When “Paprika,” the first song off Jubilee, started playing, I felt this power; it was as if the energy of her voice affirmed me and gave me immense courage.

“My heart isn’t for someone to approve, nor is it for getting more people to approve of me” -Ichiko Aoba

─You mentioned words like “anxious” and “nervous,” which relate to this special project, Because Love and Life Are Ambiguous. Music has a lot of power. No matter who you are, it’s there for you in life, which is often beyond your control and doesn’t always go your way. This is a big question, but how has music shaped your lives?

Zauner: Music is my sense of purpose. Without a sense of purpose, I feel very lost. More than something that cheers me on, music is my way of understanding something difficult. That can look like trying to make sense of the grief of losing my mom or complicated situations where there’s a duality or a double-edged sword, as I wrote about in “Paprika.” In short, music is my way of making sense of the world.

─It feels like people increasingly favor black-and-white thinking and simplification. Yet, Michelle, you confront complexities and contradictions. Why is that? Ichiko used the word “energy” to describe your music, and I can also sense your energy in the way you approach complex situations.

Zauner: Because of my upbringing, I’ve never lived in a world that allowed me to be black and white. I’ve become more and more comfortable and encouraged to live somewhere in the middle of two poles, just from growing up mixed-race between two countries. I also had different jobs, so nothing in my life is overly polarized. In any situation, finding balance, comfort, and empathy within ambiguity is a part of growing older.

─Ichiko, how about you? What are your thoughts on music and living?

Aoba: When I heard the words, “Because love and life are ambiguous,” I thought about how music is an appropriate approach for things that feel unstable and beyond one’s control. This somewhat ties into what Michelle was saying. When we go through something hard or, say, have a nightmare, we’re the type of creatures that express those things creatively, due to the nature of our work. Once such experiences are reborn as music, they’re no longer just hard experiences. Through music, they are imbued with that magic.

At times, I have to face difficult memories and trauma when I create music, but once they transform into music, it becomes the most powerful and helpful charm. It reaches not only me, but also everyone who loves music, and turns into a memory unique to each person. I live my life thinking about how blessed I am to be surrounded by music.

─Thank you for answering my abstract question. When it comes to the act of creating something, can it be said that the process of dealing with difficult matters equates to the process of trying to understand the solitary, complex self?

Aoba: I live my life as a musician, so being in dialogue with my emotions in the songwriting process is crucial. Anyone can feel… helpless, and that includes me too. When that emotion is still fresh, I sometimes cry so hard I drown in my own tears. At other times, things eat away at me and make me feel broken. They make me go, “God, what’s happening?” If I were to hide how I was feeling or act like my feelings weren’t real, things might settle down temporarily, but they’d definitely come back to bite me later on.

That’s why I never ignore my heart when I start composing a song, even if there aren’t many people who could relate to me in that aspect. My heart isn’t for someone to approve, nor is it for getting more people to approve of me. As the first step in the process of creating something, it’s important to accept yourself just the way you are.

“We tend to think of ourselves as being at the center of the world” -Ichiko Aoba

─Following the topic of looking inwards through music, I’d like to ask you about how you view things outside of yourself. The title of your latest album, Ichiko, is Luminescent Creatures. This album shows that you care not only about humans, but also about nature and diverse creatures, such as whales, coral, and the galaxy. The term “luminescent” is striking, also. Why did you release this album in this specific era?

Aoba: First and foremost, I like all creatures, including humans. Since the release of Windswept Adan [Aoba’s 2020 album based on the concept of “a soundtrack for a fictional film”—the making of the album started with her conceptualizing and writing a story in the Okinawan islands, where she stayed for a long period], I’ve continued my research of the ocean and various islands, participated in rituals on said islands, and taken a glimpse into the lives of the islanders. During this process, I began to think about diversity. When I shifted my gaze to small organisms in order to look at the world, I thought, “Surely, all creatures blink or emit light when they get excited or feel alive.” And as I made the album with that in mind, I began to realize that there were a lot of things that connected to one another.

Take, for instance, a lighthouse on an island. An entire island turns into a luminescent body and says, “I’m here” towards the outside world. Yes, it’s still a lighthouse, but if you look at it from far away at sea, it can appear to be a small creature saying something. It can resemble a creature from when life had just begun to appear on Earth. Additionally, the red blinking lights on top of buildings are sometimes used to signal that the buildings are there. I want to reexamine the many signals we’ve inherited from ancient times, which actually exist in our everyday lives. Humans and other creatures aren’t that different, after all.

Zauner: I find that really inspiring because my work is so rooted in human relationships and dynamics.

Aoba: Michelle and I might’ve exchanged small cells when we were being photographed with our faces close together. We tend to think of humans as being at the center of the world, but there are various living things that enter and exit our skin and the air. When I start thinking of living creatures in tiny units, it makes me wonder where I begin and where I end. It confirms my love for all life.

Zauner: That’s very interesting. I’ve spoken about this in other interviews, but growing up in America, especially as a girl, I was so afraid of the violence of men, which I couldn’t understand. Unlike Ichiko, I never found refuge in nature or creatures or that kind of thinking. I find her thinking to be really beautiful. When considering her work and response, I find that my work is different from hers, and that it’s so rooted in human-centrism.

“As an older woman, I was thinking a lot about having a family and being an artist and how those things stand in conflict with one another” -Michelle Zauner

─You’ve mentioned that your latest album, For Melancholy Brunettes (& sad women), was inspired by classic literature. You examined how the notion of sadness evolved over time and discovered hope for love and labor as a result. Your debut album, Psychopomp, was informed by the passing of your mother, and in an interview, you mentioned that there was a constant fear of men in your earlier works, which you’ve just touched on. How has your understanding of love changed through making this album?

Zauner: A lot of great music has been written about violent, passionate, and intense love. However, because of my age and romantic situation, I haven’t experienced those feelings for a long time. Externally, it might seem kind of boring, as I’ve been married for over 10 years now. The songs on this album are written from an older perspective and are deeply concerned with the passage of time.

I’m trying to summarize my thoughts—I guess it’s matured. It’s very gentle. Whereas when I was younger, maybe it was more violent. That’s reflected particularly in the song, “Magic Mountain,” inspired by the book, The Magic Mountain, by Thomas Mann. It’s about a sanatorium in Switzerland where people go to convalesce from tuberculosis. The protagonist goes there to visit his cousin and ends up staying for seven years. The way time passes is very mystical, and you’re not sure if the sanatorium is actually healing or poisonous.

I saw my life on tour in this way. After my mother passed away, I became very obsessive about my work. Also, as an older woman, I was thinking a lot about having a family and being an artist and how those things stand in conflict with one another.

─Do you struggle with finding a balance between the two sides you have within yourself?

Zauner: How do I uncouple my identity from being an artist? How can I also be a good human being, friend, lover, partner, and friend? I think about this often, and a lot of the record is concerned with this.

I was a very obsessive, passionate person, and I used to think that how you love someone was connected to that. To bring it back to ambiguity, as I grow older and explore that topic in this record, I realize there needs to be a balance between that kind of intensity and a gentle sort of care. I’m trying to be clear, but it might sound convoluted…

Aoba: Whenever I think about how to live a fulfilling life as a human being, from the perspective of a musician or artist, I also experience that feeling of “I might choose another path.” I was nodding as I listened to you talk because I understand what it’s like to be confused and troubled over that.

Touring the world, studying in Korea: how going abroad changes one’s interactions with others

─For this special project, Because Love and Life Are Ambiguous, we want to consider how we can love those who are unlike us, even a little bit, in this world where it’s so commonplace to reject those with differing beliefs and attributes. Michelle, you spent a year in Korea after the publication of Crying in H Mart, and Ichiko, you’ve been playing shows in countries across the globe for half a year. What sort of changes did your relationships with other people undergo after going to different places?

Zauner: After spending a year in Korea, I truly came to understand a different way of showing love and affection. In the US, we’re physically and verbally affectionate with one another. Because I was raised by a Korean mother and an American father, the way I was raised was sometimes confusing to me; it was such a contrast to the way my peers received affection from their families. But I became much more comfortable with a more subtle type of love.

I think there’s a Japanese word for this, too, but in Korean it’s “nunchi” (눈치). You clock what people say, save it for a later time, and then show up for them rather than verbally affirming them all the time. I found that to be deeper and more meaningful later in life.

Aoba: I’ve been visiting a lot of countries on tour and thus naturally, meet people with values that are completely different from mine. I learn a lot from such encounters. Even with my touring crew, when something happens, some of them go, “Fine,” while others go, “Oh my god!” Everyone is just so different that I can’t help but look upon them fondly.

─It’s nice that you can look upon them fondly.

Aoba: When there are two opposing opinions, I don’t take sides, but I don’t stand by and watch either; instead, I try to think, “I wonder what made this person feel uncomfortable?” and “What’s the backstory?” This type of training is accompanied by a great deal of imagination.

For instance, when I talk to the involved parties, it becomes very clear that they are who they are today due to their upbringing, the impact of racial discrimination, and the history of their country’s customs and culture. I’ve also felt distressed on tour before. I’ve discovered forgotten trauma from my past, for example—it’s like therapy. It’s great. Although we all love music, our experiences differ. But what’s important is not to close your heart, even when you disagree. When I observe my bandmates and crew, my perception of them changes; it’s something that gets updated.

─Having the capacity to change your mind and your impression of other people is essential when it comes to relationships. I feel like you close off the possibility of change when you cut someone out of your life.

Aoba: Totally. Being on tour has reconfirmed to me that it’s better to take the time to face something head-on, even if it’s hard, than to lie or look the other way.

Zauner: I felt like I could embody a different personality for a year while living in Korea, which was exciting to me. I’m a very straightforward, aggressive, and loud person. Very American. But because I was linguistically limited, I had to become a really good listener. I was unable to communicate everything, and I was also confronted with the fact that it’s not so important to say a lot. Finding that new gentle personality was fascinating.

“No matter how different your personalities or values are, you can come together once you choose to enter the station of music” -Ichiko Aoba

─Learning about the multiplicity of your identity could help you see how other people are also made of multiple facets. What do you think about accepting others you disagree with?

Zauner: For Melancholy Brunettes (& sad women) is about this topic. When I wrote this record, I pictured people who are not only different, but may even hate you. I think it’s necessary to try to understand those people in order to change the way things are.

For instance, “Mega Circuit” is about a group of men who wish to cause harm to women, which is also a big problem around the world. Unfortunately, it’s very necessary to have compassion, imagination, and understanding if we want to reach them.

At least in the US, we’ve politically isolated that group so much that they’re going further and further into conservative ideals. And so, it’s important, even in the face of someone who violently hates you, to try to understand and reach them because it’s the only way to bring them back to their senses.

Aoba: I believe there are so many forms and expressions of love, and although there are some things I can’t fully understand, I also want to keep trying to understand the other person as much as possible. With that said, there will always be people with whom you can’t see eye to eye, no matter what you do. In such cases, I’m learning that it’s important to watch over them instead of trying to force them to understand you. Expressing how you feel is a good thing, but depending on the time and place, you might expend a lot of physical, mental, and emotional energy. You gain nothing if you crumble as a result of that. I believe that some things become clearer to you when you distance yourself a bit and stay still, much like observing something from a fixed position.

─It’s important to distance yourself at times, rather than attack someone to protect yourself. There’s more than one way to interact with someone.

Aoba: In my 35 years of living, I’ve learned that although it’s very important to try to understand others, I can’t do that if I don’t have enough space within myself. It’s only after I forgive and heal myself that I can finally have the capacity to understand others. I’m in the middle of training myself to do so, and there are instances where the other person notices that I’m changing, and that, in turn, changes something in our dynamic. The same can be said about various conflicts worldwide.

I believe we shouldn’t be fighting wars. No matter how far we are from a warzone, the fact of the matter is, bombs are still being dropped and people are still dying. As long as this is happening, we can’t avoid thinking about it. We all live in the same world, together.

What I thought about as we spoke today is that Michelle and I think about different things, and don’t necessarily agree on everything, but we’re both enveloped in this big thing called music. I feel like music plays the role of a big station. Not just musicians, but people from all walks of life live with music. No matter how different your personalities or values are, you can come together once you choose to enter the station of music. That’s the way I see it.

Even if I didn’t look that deeply into issues arising from gender differences, Michelle, as a fellow musician, could discern and translate said issues into music, which is the most easily understood lingua franca. By doing so, I believe we can understand one another in a deeper and genuinely kinder way, more so than just talking. Let’s say there’s something that makes us both think of the other and go, “What?” If we start talking about that topic, we might misunderstand each other. But because we have music between us and initially met because of it, music acts as something that envelops and protects us.

I was discussing this with Michelle; I feel that Because Love and Life Are Ambiguous is a theme that can be interpreted in many ways because the words “love” and “life” sit next to each other.

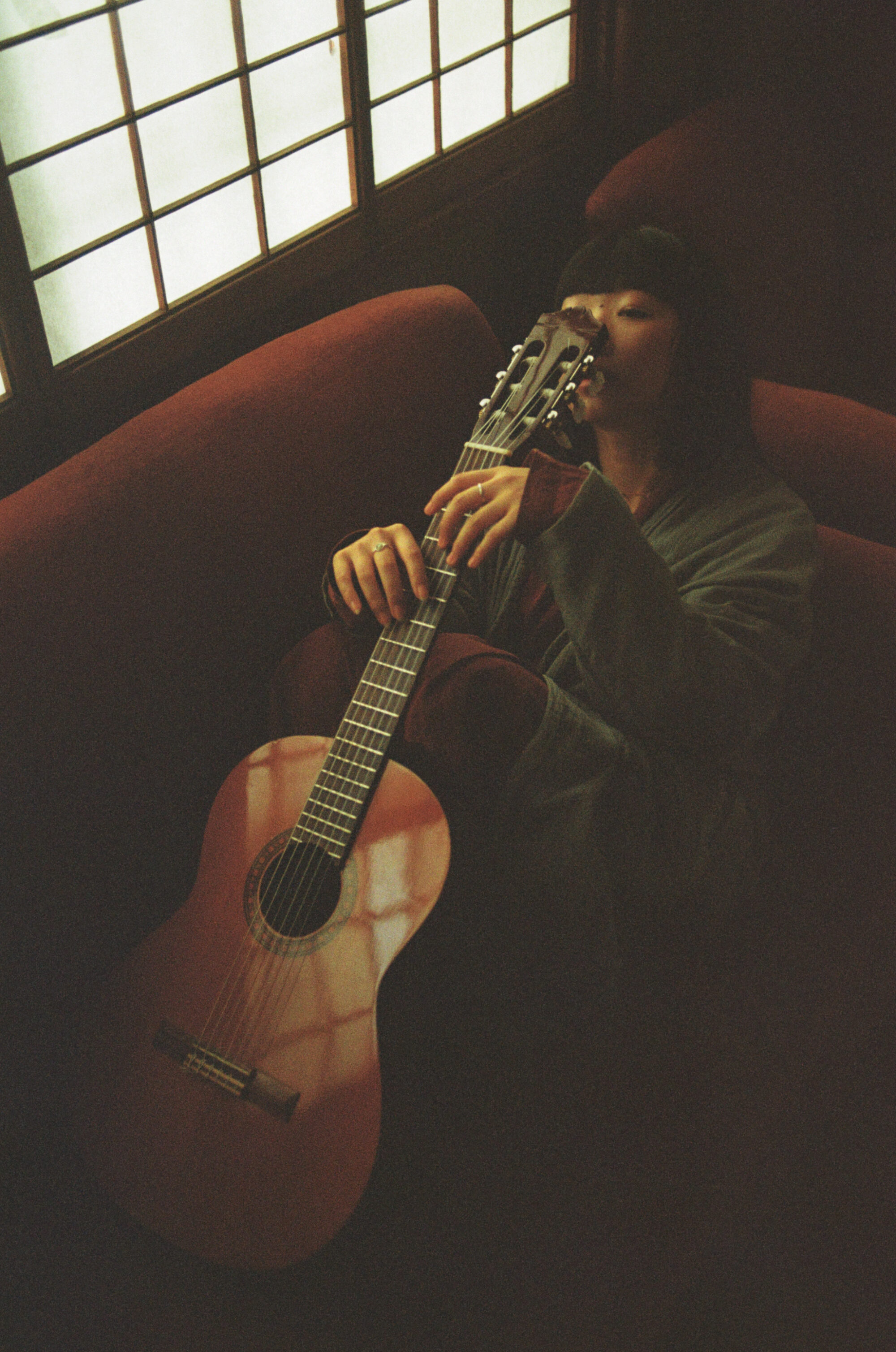

Ichiko Aoba / 青葉市子

Since Ichiko Aoba’s 2010 debut, Razorblade Maiden, the Japanese singer-songwriter-multi-instrumentalist has released seven albums, founded her independent label hermine, has performed in a growing list of territories worldwide. Her music, often composed on just her classical guitar or a simple synthesizer, is simultaneously intimate and boundless; fragile and unyielding; virtuosic and understated.

Her seventh album, Windswept Adan (2020), introduced lush orchestral arrangements to create a “soundtrack for a fictional film” that took the world by storm. From TikTok to internet music forums, Windswept Adan revealed the breadth of Ichiko Aoba’s worldwide appeal. Yet her live performances are often stripped down affairs – guitar and voice, unadorned – that still manage to captivate and enthrall audiences.

2025 saw the release of her eighth album, Luminescent Creatures, a work that developed the musical and thematic motifs of Windswept Adan, while incorporating more sparse arrangements, much like her earlier albums. Acclaimed by critics and embraced across both traditional media and digital communities, the record marked a new peak in her career.

The album sparked a two-year world tour that has included iconic stages such as London’s Royal Albert Hall, the Sydney Opera House, and Walt Disney Concert Hall in Los Angeles, with some performances incorporating up to 11 musicians on stage.

Alongside her albums and tours, Ichiko’s creativity spans many fields: radio, narration, and film composition. Her soundtrack for Amiko (2022) received Best Soundtrack at the 77th Mainichi Film Awards, and she was honored with the ANCHOR Award at the 2023 Reeperbahn Festival.

At the heart of it all, Ichiko Aoba’s music remains a space of stillness and imagination – inviting listeners into worlds both real and dreamed.

Michelle Zauner / ミシェル・ザウナー

Japanese Breakfast is the musical project of Korean-American musician Michell Zauner. Jubilee received two nominations, for Best New Artist and Best Alternative Music Album, at the Grammy Awards due to its light dream pop sound contrasted against incisive introspection. Her memoir, Crying in H Mart, became a New York Times bestseller. Zauner performs widely at international music festivals, such as Coachella and Fuji Rock Festival. In her band’s latest release, For Melancholy Brunettes (& sad women), she thoroughly explores melancholy and poetic sentiments, making her a figure who bridges the worlds of pop music and literature. Her Japan tour, which spanned Tokyo and Osaka, took place in June 2025 and was a major success.

(Photography:Pak Bae)

Profile

Ichiko Aoba – Luminescent Creatures

Release date:February 28th, 2025 (Friday)

Price:Vinyl record: 4,400 yen (tax included)

Label:hermine

Tracks:

1. COLORATURA

2. 24° 3′ 27.0″ N, 123° 47′ 7.5″ E

3. mazamun

4. tower

5. aurora

6. FLAG

7. Cochlea

8. Luciférine

9. pirsomnia

10. SONAR

11. Wakusei no Namida

Japanese Breakfast – For Melancholy Brunettes (& sad women)

Release date:March 21st, 2025 (Friday)

Price:CD: 2,750 yen (tax included), LP: 6,380 yen (tax included)

Product number:CD: DOC425JCD LP…DOC425JLP-C5

CD: Simultaneous worldwide release, with commentary/lyrics/translation, Japanese edition bonus track included

LP: Simultaneous worldwide release, with commentary/lyrics/translation, bonus track “Young Gun” download included, limited edition colored disc

Label:Big Nothing/ULTRA-VYBE

Tracks:

1. Here is Someone

2. Orlando in Love

3. Honey Water

4. Mega Circuit

5. Little Girl

6. Leda

7. Picture Window

8. Men in Bars (Feat. Jeff Bridges)

9. Winter in LA

10. Magic Mountain

11. Young Gun*

*Japanese edition bonus track (CD)

Release Information

Hoshizuna tachi,

Author:Ichiko Aoba

Publication date:May 29th, 2025 (Thursday)

Price:2,200 yen (tax included)

Publisher:Kodansha

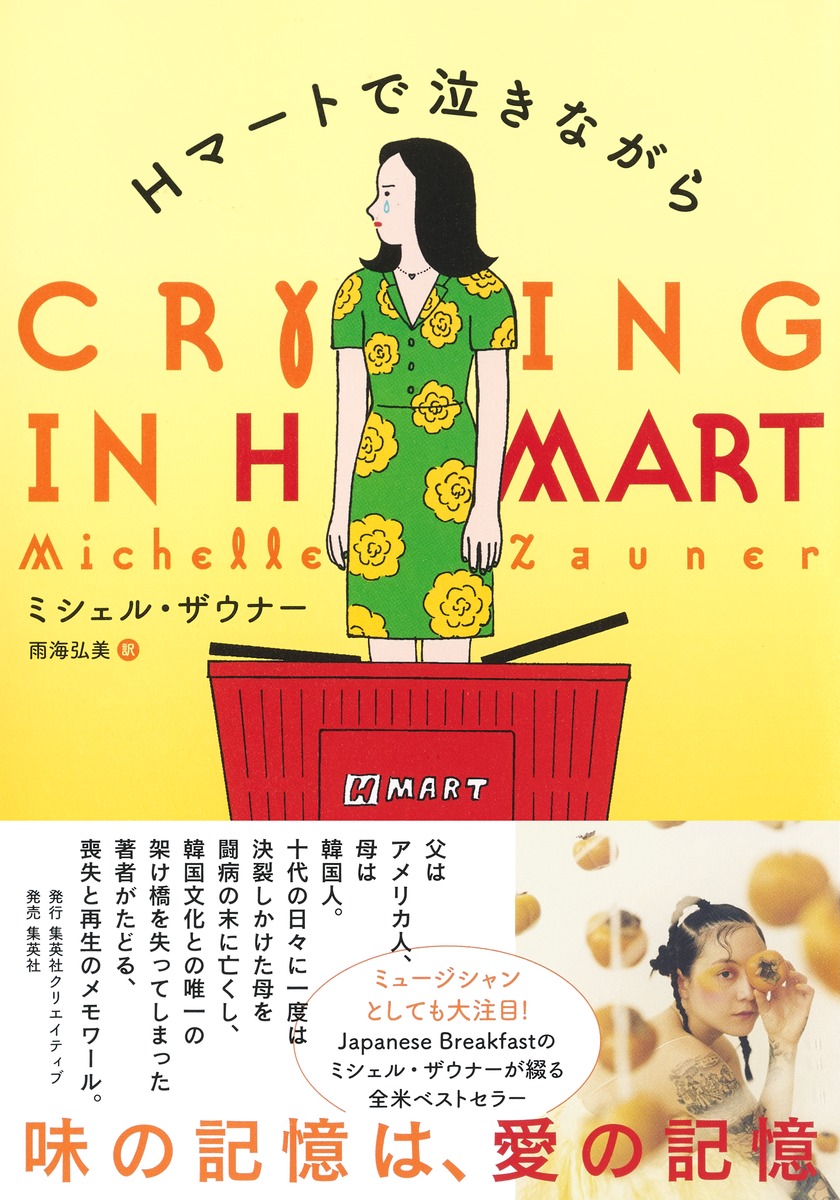

Crying in H Mart

Author:Michelle Zauner

Translation:Hiromi Amagai

Publication date:October 26th, 2022 (Wednesday)

Price:2,200 yen (tax included)

Publisher:Shueisha

Book Information

newsletter

me and youの竹中万季と野村由芽が、日々の対話や記録と記憶、課題に思っていること、新しい場所の構想などをみなさまと共有していくお便り「me and youからのmessage in a bottle」を隔週金曜日に配信しています。

me and you shop

me and youが発行している小さな本や、トートバッグやステッカーなどの小物を販売しています。

売上の一部は、パレスチナと能登半島地震の被災地に寄付します。

※寄付先は予告なく変更になる可能性がございますので、ご了承ください。